Across the weekend of the 26th and 27th of October, Nabari (Mie Prefecture) held its autumn festival, celebrating the year’s good harvest and praying for a similarly good harvest in the coming year. In Nabari itself this festival was said to have been started by Takayoshi Todo, the ruler of the area, in the 1600s and has continued to be enjoyed to this day nearly 400 years later. It was the one time a year when commoners were allowed to don samurai attire and parade through the town. This year, the mayor and other officials acted as the celebrants carrying the torch procession that would light the bonfires, to send thanks for this year’s harvest and usher in the upcoming year’s bounty.

Before the bonfire and torch procession, vendors set up stalls along the side of the roads selling all kinds of things such as food, drinks and knick-knacks creating a lively family-friendly atmosphere.

A Night of Fire and Dance

I read that the bonfire was set to start at Urufushine shrine at 8:00 pm, so I thought I should get there around 7:30 in order to find a good place to view the bonfires. But by the time I got there, the festival was in full swing. Many people were already gathering around the bonfire area and shrine, but the torch procession hadn’t made its way to Urufushine shrine, so I decided to check out the surrounding area.

There was something rather magical about the autumn atmosphere; the buzz of various stalls hawking their wares along the street, the pitter-patter of children playing and running ahead while the rest of the family trails behind, the smell of fair-style food wafting on the breeze, and the serene stillness of the shrine itself set against the rapidly darkening sky.

When the torch procession arrived and it came time to light the bonfires, I was half-expecting a controlled and measured burn, the four bonfires to alight in order and progress in a disciplined manner. Almost as if the influence of the sacrosanct environment around us would curtail nature itself and enforce a calmness on the flames. Oh, how wrong I was. The bonfires, once sparked, combusted into four towering infernos in the blink of an eye. Flickering flames danced in the structures, radiating an oppressive and intense heat.

It was in this heat, only a short distance away from the bonfires, that the shishimai or “the lions dance” was performed. A team made up of 2-3 people don a cloak and lion mask, moving and dancing in front of the crowd. It is believed that this dance is performed to drive away bad luck. I saw those same children that were running around before, transfixed in both fright and delight, as the lion weaved its way to and fro in front of them. The dance, consisting of short sharp and very deliberate movement, contrasted with more wild and unpredictable leaps of the flames. Perhaps this was not the point of the celebration but to me, the harmony that was created from these juxtapositions was the most beautiful form of worship and thanks-giving.

Joining the Mikoshi Procession

On the 27th, I had the privilege of taking part in Mikoshi or shrine-carrying. Mikoshi are portable shrines that are used when enshrined Deities are moved from one place to another or when they are brought out for blessings. As befitting Deities, the shrines are ornately decorated in precious metals and intricate carvings, but this also means that these Mikoshi are extremely heavy with some being over 1,000 kgs requiring a team of people to share the weight and carry it together. This group effort is meant to bring the community together as a show of unity and purpose.

Usually the people carrying it are locals, who live in the area of the shrine in question. Since this ritual seemed to be rather important, I had imagined that this was a tradition that spanned generations, with a family doing it until they were too old and frail then passing on that responsibility to their children and so on. For this reason, I was slightly apprehensive about joining in. Even though I live in the area, had I managed to put myself into the community enough to actually be “local”? I would feel fine about showing up and just watching, but participating especially in something that was seemingly as reserved as shrine carrying, was another matter entirely. In the end I decided that in order to fully dive in and become one of the communities, I would have to take these opportunities as they presented themselves.

However, when I asked around the office, I was definitely surprised to learn that most people I asked had never done it before. Especially in a small town like Nabari, I imagined that they would get as many locals as possible, getting volunteers from high schools and the like. I thought that it was something like the annual A&P (Agriculture and Produce) show in Christchurch, New Zealand, where even if you don’t have a booth or event, you surely would have attended it and helped in some capacity, like going to it as an elementary school trip. This was definitely not the case.

The Mikoshi March Begins

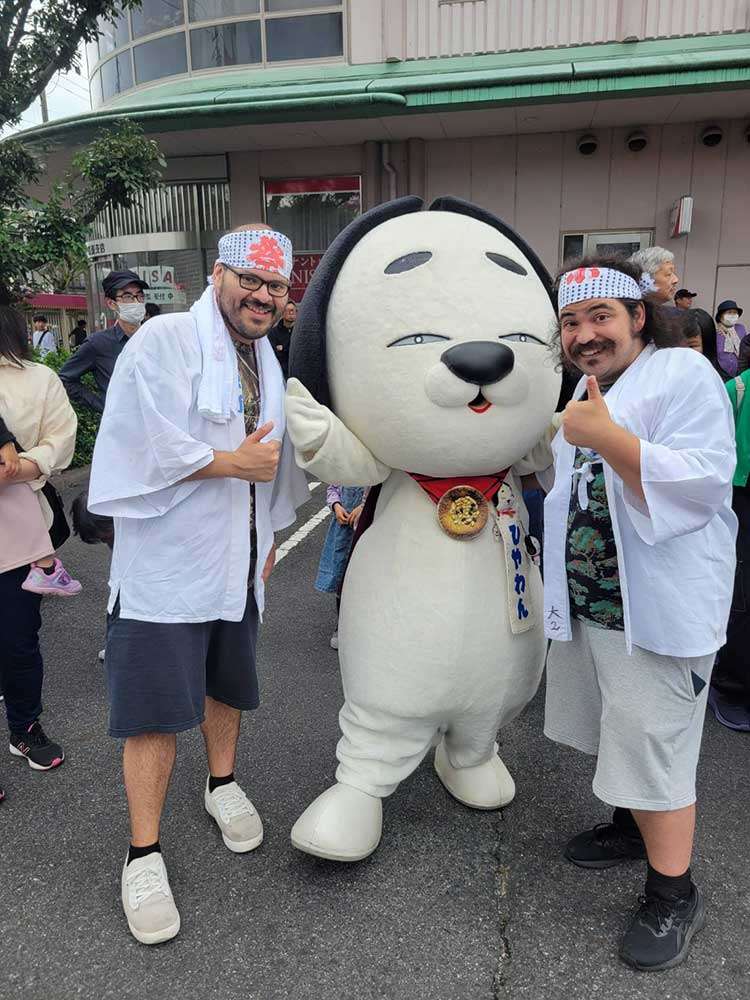

At a bright and early 7:45 am on a Sunday morning I left home to walk to Ebisu Shrine, the gathering point for my group, and I met up with another ALT (Assistant Language Teacher) Jonathan, who was joining for the first time as well. When we got to the shrine, the organisers of the group were already outside busy getting people ready and making sure the shrine was well prepared. We were immediately ushered into a nearby house and immediately kited out with white happi (a traditional Japanese coat warn at festivals) and headbands with the word for festival written in kanji. It’s honestly amazing how much putting on the outfit really puts you into the festival mindset. With it on, I was ready to hoist any burden, shoulder any weight, walk any distance!

Accompanying us on our walk was a costumed tengu and his two henchman oni. When I asked about them, I was told that they would go inside some shops along the route to get receive tithes in exchange for blessing the store with good fortune in the upcoming year. While they were inside, we were to shake the shrine and yell loudly to rouse and amuse the god inside the shrine in order for it to give its blessings. The instruction of shaking it seemed very difficult even with all of the team. I certainly was worried about the shrine dropping before and even more so after hearing we had to shake it. What would happen if it did fall? I still don’t know because I didn’t want to voice it aloud and luckily, it never happened on the journey.

Photo courtesy of Iga Town News YOU

Photo courtesy of Iga Town News YOU

Standing at a solid 156 cm in height (5’1” for those that don’t use the metric system), I was just a tiny bit shorter than the other members of the team and so when the shrine was lifted onto our shoulders, the pole actually rested a couple centimeters above my shoulders. Still I was determined to play my part and have some contribution to the team. So I decided to do a sort of shoulder press to lift the Mikoshi (In hindsight this was not a good idea, my muscles were aching for the next week!). I felt bad for the taller members as they had to stoop down or lean to try and get the Mikoshi to be level. It would be the easiest way to disperse the weight but they definitely couldn’t get it to be down to my height without crouch-walking the entire time. Definitely an unrealistic proposition. We managed to get it situated though, and started on time at 8:30 am.

Our journey began heading to the nearby Urufushine Shrine, to keep us all in step and in rhythm, as a call-and response–style march, we chanted (In my case, I screamed it as loudly as possible).

Chosa is a local Nabari word that we use instead of the more traditional “wa~shoi washoi”. Its meaning is close to “Let’s go!” or “One, two” that some people chant when doing an activity. It’s to help people synchronize and move together, reminding us of our shared goal and giving us strength as a group.

It reminded me of the NZ Waka Ama (a type of Pacific canoe racing sport) where we would chant numbers in Maori to help us with our paddling timing. It also had the benefit of giving us something else to focus on, rather than the physical strain we were under. It felt like going into a trance, where you don’t focus on how far you’ve gone or the weight on your shoulders, just one foot in front of the other and repeating the words “Cho~sa”. For me at least, it was somewhat therapeutic.

Urufushine shrine is normally a short 5-minute walk, only 500 meters away. This time though, it took us about an hour with all the shops that we stopped at to bless.

One great thing was that they offered refreshments while we were stopped. Obviously, they had plenty of water and other drinks to help keep us hydrated but I was drawn to the sake. I was told it was traditional to drink sake when doing this as a way to bolster your spirits and strength for the journey. That was all the excuse I needed. It was really excellent sake too, going down very smoothly and providing a strong warmth in my belly. It wasn’t the focus but at definite bonus that kept me in good cheer the whole time. But don’t worry if you don’t drink alcohol, there were plenty of other options as I said, so everyone was well catered for at every stop.

Final Thoughts – An Invitation to Experience Tradition

All in all, it was well worth all the aches and pains coming from it afterwards.

If you want to participate, but like me, feel intimidated by the possibility of culturally overstepping or are anxious about not being able to speak Japanese, then please let this article assure you. Everyone there, from the participants, organisers, volunteers to the public just watching the festivities, is absolutely delighted that you are taking part. It will be a chance to interact and experience a unique part of Japanese culture directly. Even if you don’t speak Japanese, I know people will go out of their way to make you feel included.

So take a chance, take the plunge and join in! The sheer accomplishment and sense of teamwork will make you feel like the gods within the mikoshi have blessed you directly.